His subjects range from the spectacular failures of the FBI to detect spies within its midst to the gullibility and greed of investors who lost vast fortunes by trusting their money to the fraudster Bernard Madoff.

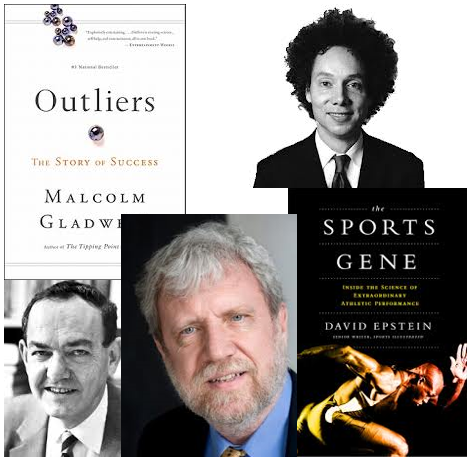

“The book is really about those disruptive influences.” “Any element which disrupts the equilibrium between two strangers, whether it is alcohol or power or place, becomes problematic,” he tells me. Unlike them, though, it lacks a single iconoclastic, zeitgeist-defining idea, instead roaming far and wide to illustrate the problems, individual and collective, personal and ideological, that dog our interactions with others in our globalised, but increasingly atomised, culture. Like the previous bestselling books that made his name – The Tipping Point (2000), Blink (2005), Outliers (2008) – Talking to Strangers is essentially an exploration of human behaviour that also challenges much of our received wisdom about that behaviour and its motivations. Gladwell’s new book is called Talking to Strangers and, here we are, two strangers, conversing over tea in a fashionable Covent Garden hotel about the difficulties that can sometimes arise when, as he puts it, “we are thrown into contact with people whose assumptions, perspectives and backgrounds are different from our own”. He is not big on small talk, and one senses that every hour in his working day is geared towards maximum efficiency. The signature afro has been tamed somewhat and, if anything, makes him look even younger. At 55, there is still something of the sporty, if slightly gawky, teenager about him his jeans and a lightweight hoody accentuate his height and wiry thinness. I n the flesh, Malcolm Gladwell is exactly as I imagined him to be: engaging, polite, dauntingly cerebral and supremely self-assured in that way that the exceptionally gifted often are.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)